Taking on a daunting task

This is my attempt to explain what I think is a good attitude to have when faced with a long, daunting task. I use a conversation with my piano teacher only as a guiding theme. I think it makes a good example.

One of my greatest passions is music, and although I’ve been listening to metal for most of my life, I keep romantic composers at the top of my list. There’s something irrational in my head that tells me that Chopin or Rachmaninoff, with whom I’m obsessed, couldn’t have written their masterpieces themselves: they must have found them somewhere, a gift of nature waiting to be picked up by a fortunate and careful listener.

This love for their music has led me to become an amateur pianist. Even though I haven’t been to school for music and I haven’t gone through the training that a classical pianist usually receives, I can’t stop myself from attempting to play Chopin’s preludes and nocturnes.

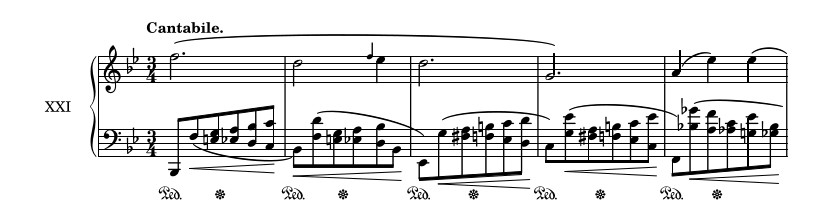

Not long ago, my piano teacher was helping me learn this prelude, and in a rush to advance through the score and learn it as quickly as I could—with the good intention of playing the whole piece as intended by the composer—I ended up groping for the notes mechanically, and it sounded unconvincing. He recommended I divide the score into simpler pieces that I could practice separately.

The melody is not complex, so I should focus on the left hand. The left hand has three voices: the bass, and then two dividing melodies in each measure. I proceeded to practice the left-hand voices separately.

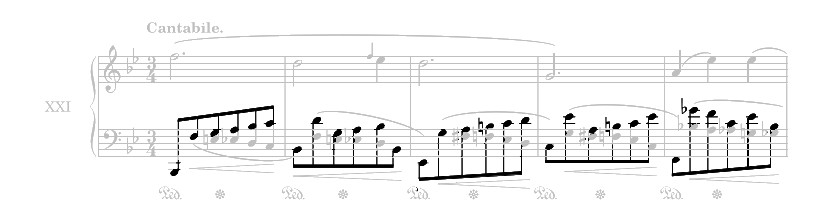

First, bass and the ascending voice:

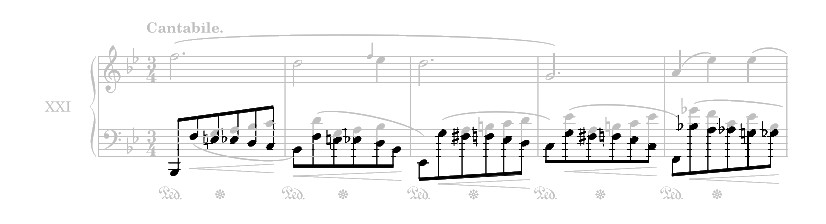

And then the bass together with the descending chromatic voice:

I wasn’t enjoying it. I wanted to play the whole thing! I hurried to play the notes one after another. My teacher saw this, so he looked at me with a face full of concern and told me something that really resonated with me. I felt like I could connect that idea to many other things. He said I should imagine each of the sections I’d divided the piece in was a new, different piece. I should play each of them as if this was what the composer originally intended to write, and play it as beautifully as I could manage to. And most importantly: I should enjoy it for what it is.

And lo and behold! I found each of the dissected melodies so great that I could listen to them on their own repeatedly, and I started to enjoy studying the prelude. Even more, I started enjoying recordings of the prelude more than before!

Can this attitude help me learn and learn to love more things apart from these pieces? Can I divide every process that may at first seem daunting and uninviting, and turn it into little pearls of enjoyment? The idea reminded me of Camus’s The Myth of Sisyphus, where he suggests that one must imagine him happy:

Sisyphus, […] who was condemned to repeat forever the same meaningless task of pushing a boulder up a mountain, only to see it roll down again.[2]

If I make an effort to slow down and appreciate every detail of what I’m doing, whatever it is, I find myself having a much better day altogether. I can feel satisfied even if I don’t see an end to something I’m doing, as long as I have fun along the way.

- Chopin, F., 2020. Prélude 21 By F. F. Chopin (1810–1849). In Mutopiaproject. Retrieved April 10, 2020, from https://www.mutopiaproject.org/ftp/ChopinFF/O28/Chop-28-21/Chop-28-21-a4.pdf

- The Myth of Sisyphus. (n.d.). In Wikipedia. Retrieved April 9, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Myth_of_Sisyphus

A note on the prelude: to some of you it may seem like learning it is not exactly a good example of a daunting task. To me, and at my level, it definitely is.